KEY TERMS: formalism; history; canon; novel; ephemera; rhetoric; Richardson; feminism; interdisciplinarity; generalist; teaching

History

For me, literary studies is necessarily an interdisciplinary field. How can I understand Sir Charles Grandison without understanding the life of Samuel Richardson? How can I understand Richardson without understanding the society that shaped him? A rich understanding of literature, then, is necessarily bound to history, but traditionally, literary scholars have leaned toward formalism and have scorned “mere causal investigation,” or historical approaches (Underwood 13). Formalists argue that really, all that matters is the text on the page, but even some formalist views are evolving to encompass history and biography. John Richetti, for example, who argues that “the main [task] of literary studies” is to analyze the literary works themselves, and that literary scholars should see literature as “distinct from other linguistic and cultural practices within its particular historical context” (157), acknowledges that the eighteenth-century novel is irrevocably intertwined with the culture that produced it, and so he favors “a new, historically oriented formalism” (159).

Rhetoric

I go a step further than goes Richetti. In addition to studying the historical context of the period, I wish to study the works of the period that have been traditionally ignored. Novels, poetry, and drama have been the accepted objects of study since the inception of English literary studies in the mid-eighteenth century (Miller 1-2), but, as the field is driven by progressive intellectuals, literary studies has questioned the literary canon for quite some time. I am not breaking new ground here. Yet, while it has become more mainstream to teach the novels, plays, and poems of marginalized and disenfranchised authors, marginalized and disenfranchised genres have not quite been brought into the fold. I acknowledge that my literary loyalties belong first with novels: My favorite works are all novels, and the novel plays a special role in eighteenth century studies, as this is the period when it became prolific. But I cannot in good conscience devote all of my intellectual energy to novels when so many important ephemeral works were published at the same time (including maps, it-narratives, trade cards, dictionaries, newspapers, tickets, travelogues, and suicide notes, among almost anything else you might imagine). Traditionally, literary scholars have considered these materials obsolete, “textual materials that may have been valued by someone at some time for some reason, but are without ‘enduring literary value’ now” (McDowell 48). After all, ephemera “is the plural of the Greek ephemeron, meaning something that lasts only for a day” (McDowell 53). Yet times are changing. How can scholars of eighteenth-century literature ignore the most prolific texts of the period (McDowell)?

I believe that I must thank the field of rhetoric for my questioning of the canon and for my appreciation of ephemeral works. For whom were these texts written? In what ways did they interact with other texts and with their intended audience? These are rhetorical questions that I think literary scholars must ask. Notably, Richardson, to whose works I have already begun to devote myself, was a printer, and the ephemeral works he printed no doubt influenced his work. (In fact, his first published writing was a collection of didactic letters, which he revised to create his wildly popular Pamela.) The connectedness of ephemeral works and novels is rhetorically fascinating, merging together not only history and culture with literature, but literature with rhetoric, as well. (And, indeed, composition—Richardson was known for his very conscious and audience-based writing and revision.)

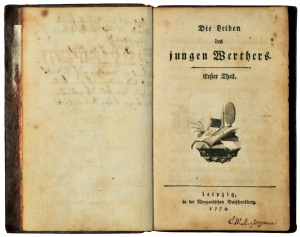

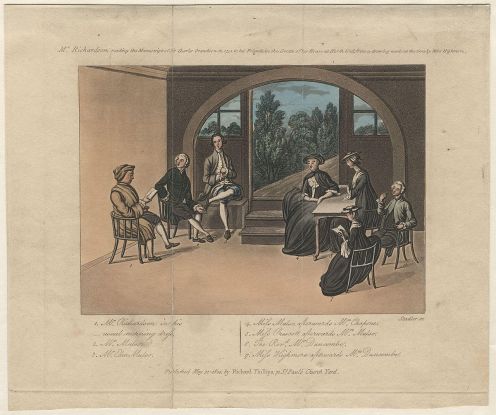

Engraving by Miss Highmore (a member of Richardson’s circle) in 1751.

In the early days of English studies, rhetoricians taught both English literature and composition. In his introductory chapter to English Studies, Bruce McComiskey explains that rhetoric, after all, had been a respected field, considered “the foundation of a liberal education” (5) in Europe since the time of the ancient Greeks and through the Middle Ages in England. By the end of the nineteenth century, though, rhetoric fell out of favor and was seen as wholly pragmatic. Now, rhetoric is a rightfully respected field, but it’s still seen as clearly distinct from literary studies. I think that rhetoric and literature both suffer from such a distinction. Each field is interesting on its own, but combining these fields opens a world of intellectual possibility.

Feminism

Obviously, I reject strict formalism, as I believe most modern literary scholars do. Formalism has slowly been falling out of favor since the 1970s due to the increasing faculty diversity that has led to the increasing inclusion of gender, cultural, and race theories in the field (Elias 223). My disavowal of formalism makes way for my guiding theory: feminism. Feminism is logically linked with eighteenth century studies, as the eighteenth century was a pivotal time for women, especially in relation to the novel. The lapse of the 1662 Printing Act led to a drastic increase of printed materials, ultimately leading to a middle class that was educated due to cheap print literacy. This meant that women, too, had easier access to printed materials, and they also had easier access to publishing. This explains the increase in published female authors, especially in the second half of the eighteenth century (notable examples include Frances Burney and Maria Edgeworth); perhaps because so many readers were women, even male authors, like Richardson, tended to focus their novels on female protagonists. Due to women’s relationship to eighteenth-century literature, then, feminist theory is essential to understanding the literature and culture of the period.

Interdisciplinarity

I believe that any modern scholar of eighteenth century literature must go beyond formalism, the canon, and even literature itself. Whether this interdisciplinarity is an intersection with cultural studies, rhetoric, creative writing, or another related field, interdisciplinarity is a must. Specialization is dying and making way for the generalist. Dr. Laura Buchholz explains:

On the whole, universities are devoting fewer and fewer tenure lines for specific period specialization lines. If you look on the MLA job list for example, you will see some ads for period specialist- Medieval, early modern, 18th century etc. However look closely and you will see how many of these span what used to be multiple periods- for example, 10 years ago a university might have a Romantics specialist, a Victorianist, and an early 20th century modernist- today these positions are combined quite often into a “Long 19th century.” Similarly I recently saw one ad where the school wanted either a professor with a specialization in either 18th or 19th century lit who could teach courses in both centuries.

My interview with Dr. Buchholz was enlightening. A period specialization is still “deeply entrenched,” but a scholar who focuses only on a period may be seen as irrelevant; instead, Dr. Buchholz says:

Universities are looking for period specialists, with supplements—so you find an Early Modern scholar who also does digital humanities, a Modernist who works in narratology, a Victorianist who also does gender studies etc. As a result, departments are getting an eclectic mix of specialties where individual scholars wear many hats, become more and more interdisciplinary and, as a result I believe, produce some very interesting work that is far less rooted in a particular “period” than it might have been a decade ago.

These scholars, then, are generalists, and a generalist needn’t be someone who has only a topical knowledge of many different subjects or who is simply the “product of a withering job market” (“2 Literary Generalists”). Instead, a generalist is someone who has a deep understanding of how different fields, subfields, and bodies of knowledge connect. I looked to The Chronicle to understand views of the English generalist, and I found an interesting account of Paige Reynolds’s experience. Instead of focusing on a specific period from the beginning of her graduate studies, she decided to study whatever struck her fancy. Instead of hurting her, she claims that this actually made her a more attractive professorial candidate: “[M]y ambivalence about an academic career shaped my tenure as a graduate student in ways that appear to have made me a stronger applicant. Here’s what I learned on my job hunt: Disregard [s]trategy and [d]o [w]hat [y]ou [l]ove.” She adds:

[O]ne piece of advice I’ll offer based on my experience is to try to pitch your research project toward a few different areas. One chapter on women won’t land you a position directing the women’s studies program at your dream college, but if you can demonstrate competence in different arenas, all the better. I had a distinctly Irish dissertation, which made me ripe for Irish-studies positions. But I didn’t want to preclude more generalist positions in 20th-century British literature, so I taught modern British literature surveys and published a paper on Wyndham Lewis to demonstrate to hiring committees that I could teach and produce research on topics outside of Ireland.

I want to dedicate myself to studying literature, but I don’t want to get so wrapped up in novels and poetry that I neglect ephemeral, marginalized works or the political and social movements of the period, and I don’t want to become so absorbed in the dominant culture of the eighteenth century that I neglect colonialism.

I recognize that these ideas are all interconnected; I see my job as a scholar to make meaning of this connectedness.

Teaching

But I’m not making meaning only for myself. I want to write—what English major doesn’t?—and I want to publish, but, as I am a community college instructor, teaching is at the forefront of my duties and desires. Traditionally, Jacques Berlinerblau says, humanities professors “are fanatically and fatally turned inward. We think and labor alone. We write for one another”; an English studies generalist, however, is a scholar “who translates material not on the page, but through exciting teaching” (“2 Literary Generalists”), because “conveying knowledge is as much a part of our craft as attaining it is” (Berlinblau).

That’s where I am now. I enjoy digging deeply into eighteenth-century literary issues in my writing, but the deepest sense of fulfillment comes when I’m able to find connections and introduce the material to my students. I teach at a community college; I know that very few of my students will ever even consider becoming English majors. (I’ve been teaching for five years and not one of my students has majored—or minored—in English.) But I try to find ways to meaningfully engage my students in literature, and I often do so using interdisciplinary approaches.

For example, I (briefly) introduce students to literary theory in my Introduction to Literature course (which also doubles as the second part of my school’s FYC sequence). One theory we discuss is feminism, and I always find it exciting to introduce my students to Mary Astell’s rhetorical power via snippets of Some Reflections upon Marriage. I’m able to use this as an opportunity to teach the syllabus-mandated literary theory, to help students apply the theory to literature we read in class, and to show students ways to compose powerful prose of their own.

To my mind, this is exactly the sort of skill my generalist track at ODU will help build. As teachers, we have all had those class sessions when everything just fits; one subject flawlessly segues into another, then another, then another, and the teacher and students alike all have a better understanding of each subject than they would if the subjects were taught in isolation. That seems to be what interdisciplinarity is about—covering vast ground in order to understand deep connections—, and it’s those moments that I want to work hard in this program to create both for myself and for my students.

So who am I as a scholar? Where do I see myself fitting into English studies? I want to cross boundaries, but I don’t want to do it alone. For me, studying literature is not an act of introversion. I want to bring my students along with me. My best work, I think, won’t be found on the shelf of a prestigious library, but in the words and ideas exchanged with my students every day when we step into our shared classroom space.

I want to be a historian, rhetorician, and feminist, but above all, I want to be a teacher.

Works Cited

“2 Literary Generalists Prepare to Defend Themselves in a Book.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 20 Jun. 1997. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

Berlinerblau, Jacques. “Survival Strategy for Humanists: Engage, Engage.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 5 Aug. 2012. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

Buchholz, Laura. Personal interview. 20 Sept. 2015.

Elias, Amy J. “Critical Theory and Cultural Studies.” English Studies: An Introduction to the Discipline(s). Ed. Bruce McComiskey. Urbana: NCTE, 2006. Print. 223-274.

McDowell, Paula. “Of Grubs and Other Insects: Constructing the Categories of Ephemera and Literature in Eighteenth Century British Writing.” Book History 15 (2012): 48-70. Web. 4 Oct. 2015.

Miller, Thomas. The Formation of College English: Rhetoric and Belles Lettres in the British Cultural Provinces. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 1997. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Reynolds, Paige. “The Academic Job Market: A Guide for the Ambivalent.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 30 Jun. 2000. Web. 27 Nov. 2015.

Richetti, John. “Formalism and Eighteenth-Century English Fiction.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 24.2 (2012): 157-160. Web. 18 Oct. 2015.

Underwood, Ted. Why Literary Periods Mattered: Historical Contrast and the Prestige of English Studies. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2013. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.